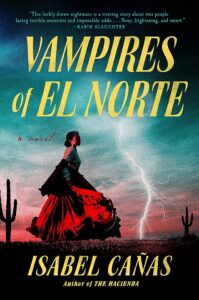

It’s Dia De Los Muertos, Day of the Dead, and what better way to celebrate than with a book review of Isabel Canas’ excellent second book, Vampires of El Norte about the undead. In many ways, this second book, still in the Mexican Gothic vein, shows a maturity of subject matter and writing style different from her The Hacienda. However, I must ask the author, “who did your novel’s dust jacket?” Saguaro cacti are in Arizona, not the RGV. Perhaps the background should have been ocotillo, as befits the novel you have exquisitely created. Take care that your publisher does not a continue to depict the area erroneously as most Americans are prone.

The setting of Vampires of El Norte is different from The Hacienda: now set in the Rio Grande Valley of what would become south Texas and the year is 1837, many years after the first blush of Mexico’s independence from Spain. All Mexican citizens both north and south of the Rio Bravo, aka, Rio Grande River, are bracing against encroachment of white U.S. settlers moving south from the original Texas border of the Nueces River, near Corpus Christi. These white, American settlers are poaching the Mexican rancher’s cattle and creating an unsafe environment within the Republic of Mexico. Caught between the original Texas boundary of the Nueces River and Mexico City, thousands of rancher settlements struggle to maintain their hold on land ceded to them from the fourteenth century. Imagine if hordes of rabid Canadians invade our northern borders with the expressed intent to land grab. Now imagine yourself in the boots of Canas’ Mexican characters trying to deflect a bunch of rabid white, slave-owning Americans who are intent not only of land grab, but also the extension of slavery for southern political expansion. This was the real situation just prior to the Mexican War which aggressively pushed Texas borders way past the Nueces into the heart of Mexico and with murderous intent. Think about those events, less than 150 years ago, when you are complaining about today’s southern border problem…a problem in which the U.S. is totally complicit.

The author paints a lush and atmospheric landscape where the larger cattle ranchers and the small Mexican ranchers lived as with most rural Mexican areas in a social hierarchy based upon land, cattle, and horses. From this setting, we meet the big rancher’s daughter Nena (short for Magdalena) and Nestor the landless vaquero who hires his cattle and horse services to the large ranches. The two young people fall in love, but social hierarchy dictates that Nena must wed another large rancher’s son to build their families’ holdings. Still in their teens, Nena is attacked by one of the area’s growing population of vampires and Nestor flees, returning several years later to a more mature Nena. After several years of thinking each was dead from the attack, Nena and Nestor reunite. Strong social hierarchy injects itself again between the two main characters, but Nena is determined to be with Nestor who wants to purchase his own land for ranching. Please note, that in Mexico it was illegal to own slaves. The fact that the invasive white settlers, enthusiastically embrace slavery is again characterized by not only the vampire’s existence but it is also implied that these vampires were slaves of the U.S. settlers. Indeed, Nena takes piety on the shackled vampires and gingerly frees them, a kindness that they later return to her, allowing her to return, once again, to her beloved Nestor.

Eventually the whites with their vampire slaves will overtake the Mexican population and expand, illegally and with aggression, the state of Texas. I am enamored with the author’s portrait of the Rio Grande Valley (RGV) during this time. Her author notes are particularly interesting “The Rio Grande Valley is a pocket of the world where the border has moved more often than the people living there.” She recalls a recent RGV visit with her grandparents, “filled with the sounds of cicadas and chachalacas…” And I recall my first memories as a three-year-old sitting on a blanket in my parents’ back yard with my baby brother and the scolding screeches of the chachalacas in Brownsville followed by the non-stop buzzing of cicadas in the afternoon heat. Fifteen years later and having roamed every blessed place between El Paso and returning to Brownsville I found that nothing really changed. Several decades later, having buried both parents and brother, the RGV remains as “a pocket of the world” where the border is fluid and the memories rich. On this Dia De Los Muertos I intone blessings to my dearly departed in Boca Chica, near Brownsville, Descansa en paz y vaya con dios.