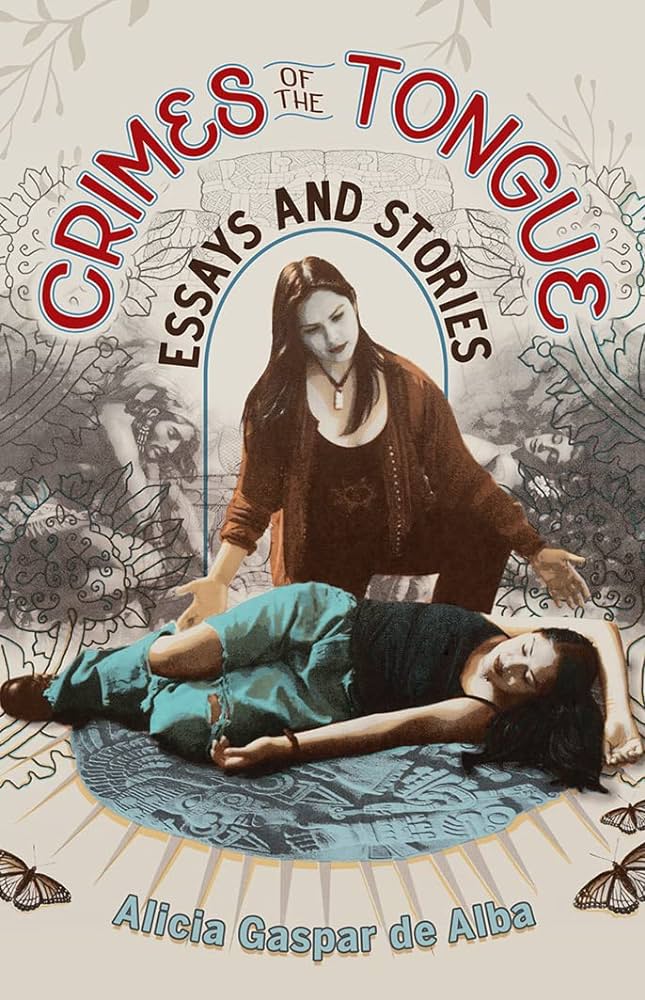

At last, the writer and academic, Alicia Gaspar de Alba, has finally published a rich composite of her essays and stories about our borderland. Born in El Paso, she was raised in both El Paso and in Ciudad Jurez with “a forked tongue and severe case of cultural schizophrenia, the split in psyche that happens to someone who grows up in the borderlands between nations, languages, and culture.” Gaspar summarizes our dilemma in La Frontera very well. To illustrate some of the “cultural schizophrenia,” the book cover of Crimes of the Tongue is art from Gaspar’s wife, Alma Lopez. The two women in the foreground depict a Pieta scene with a Mexican mother lamenting the death of her daughter whom she tried to shield from the violence and sexual abuse so rampant along the border. However, it is the figures and symbols in the background that depict the genesis of the Mexican/Mexican American women’s dilemma. According to legend, when the first Spaniards arrived in Mexico, the Aztec Emperor mistook Conquistador Hernan Cortez as the long-prophesied reincarnation of an Aztec God. The Aztec Emperor, before he realized his mistake, gave Cortez gold and silver and a harem of noble Aztec women. One of these women became the translator between Spanish conquerors and the Aztec leadership. Ordered by the emperor to give Cortez what he wanted, she translated all the Aztec defense secrets which caused the downfall of the Aztec Nation and the rise of the oppressive Spanish Conquistadors. But that was not all Cortez wanted. Cortez raped the interpreter who later gave birth to the first Mexican, Martin Cortez. This Mexican Eve, called La Malinche was initially demonized by Mexican writers as being a traitor for her translation work, or crimes of the tongue. As a revisionist of Mexican feminism, Gaspar and her Chicana colleagues see La Malinche as a victim of colonization and patriarchy. The modern “Mexican Eves,” continue to struggle against family, social and workplace oppression to live the best they can and provide for their children under harsh conditions. Consequently, the origins of the Mexican, feminine prototype are rooted in the destruction of indigenous Mexican culture and the lingering post- colonial systems of oppression. The book’s cover blends Ancient Aztec glyphs and symbols; the rape of the indigenous woman; the Catholic pieta scene; and finally, the miracle and hope that is the butterfly, the mariposa.

Gaspar’s anthology should be read by both women and men who are looking for the origins of the border crisis and the origins of the Mexican personality, which is feminine, not paternalistic. Crimes of the Tongue has many different meanings which Gaspar illustrates. However, I’m drawn to the image of the mariposa; and not just any butterfly. It is the Monarch Butterfly who roams all North America. However, it is the tropical rain forests of northern Mexico that is its nursery and grave that all Monarchs migrate towards. In between birth and death, they are sustained by floral nectar, extracted by their long tongues until they return to Mexico to give birth and die. Beware, Monarchs are rapidly losing population and border on extinction.